For many people who work in STEM, and especially those in research, science communications or ‘scicomm’ has become an essential part of their job. But if you’re not already engaged in scicomm, should you start?

For many people who work in STEM, and especially those in research, science communications or ‘scicomm’ has become an essential part of their job. But if you’re not already engaged in scicomm, should you start?

Why communicate science?

Science is in demand: Journalists are always looking for stories, politicians and campaigners need information to develop policy, fellow citizens want to understand the world around them, and entrepreneurs are looking for new products. STEM research has never had such a wide and varied audience.

On the other side of the coin, STEM institutions are realising that clear and accessible communication of their research is essential to building good relationships with – and gaining the approval of – their communities. Funders are also seeing the value, and frequently request that grant applicants explain how they are going to communicate their findings to stakeholders and the public. And employers, whether in academia or industry, increasingly recognise the importance of scicomm skills and will look for, and expect to find, evidence of STEM communication on your CV.

And of course, many people who add a communications angle to their work find it affirming and enjoyable, and it reminds them of why they went into STEM in the first place. So if you want to expand your skillset and make your CV more attractive, it’s certainly worth acquiring some scicomm skills.

Where to start?

The first and most important think that you need to decide is who you want to talk to. Who is your audience? Are you talking to colleagues, other scientists in your field who use the same jargon and who are already familiar with the ideas and concepts you want to discuss? Or do you want to be more of an advisor, sharing information with those who lack it and seek it, for example, the panel members of a parliamentary enquiry who need explanations in everyday language? Or would you prefer to be talking to the general public, demystifying your area of expertise, putting current affairs into context, and helping people understand the research being published in your field?

The kind of STEM communications you want to do, the audience you want to address, and your relationship with them will change where you start and how you develop your new skills. Getting the roles and relationships right is the first step to effective communication.

Deciding on your strategy

So, consider these questions when you face a STEM communication challenge, and keep your answers in mind as you prepare. Even for the simple task of giving a talk, you need to know:

- What is the purpose of the exercise and of my contribution?

It could be educating, advising, campaigning, developing policy, lobbying, pitching, selling, entertaining, sharing or listening, or some combination of these.

- Who am I talking to?

Are they older or younger, senior or junior in rank, experts in your subject or not, preparing for exams, personally affected, knowledgeable and passionate activists, people who share your values or hold different ones … ?

- What kind of space and size of audience will I face, and for how long?

A small group around a table for two hours, a lecture hall full of people for 40 minutes, or science festival participants should they choose to stop at your stall for a minute or two?

- What is my role on this occasion?

Are you an expert armed with facts, an advocate aiming to persuade, an advisor offering suggestions, or a fellow citizen looking to share knowledge and learn from others?

Once you have clear answers to these questions, your communication strategy will emerge.

For example, imagine that you are an engineer, and you have been asked to visit a school to meet 12 teenagers who are thinking of studying engineering. You will be expected to advise them, but also to keep them entertained (they expect both of these from adults in their school). You can find out from the school what stage of their education they have reached (what choices are still open to them?), and what their cultural backgrounds are (are family members likely to be professionals?). You have been given a slot at a lunch-break – 40 minutes, after the students have eaten (they may be wishing they were outside). You are an expert with experience (and so can offer stories about the exciting and important jobs you and your friends do), but you also want to be a possible future colleague for the young people (so you are accessible and congenial). You are different from them now, but you are inviting them to become your equals, and so you make that seem possible.

Sharing your expertise, and learning from others

STEM professionals are valuable to society because of their expertise. It is their job to know about their subject, and to recognise that other people reply on them for this knowledge. But at the same time, where many people are affected by the outcomes of scientific knowledge, we should recognise that their own expertise and experience that may contribute to better understandings overall, and to more cohesive and equitable collaborations between science and society.

Developing communications skills and confidence, whether that’s in public speaking, writing, podcasting or media appearances, will help you develop your broader STEM career. Many learned societies provide training, and there are plenty of courses and resources available online. Talk to people who have had some practice and learn from them. Find out about your local science festival and offer to help. Read science blogs, listen to podcasts, follow science communicators on Twitter or Facebook, and think analytically about what you see and hear – what was fun, what was interesting, what was clearly explained (and how)?

Start a Twitter account, Facebook page, blog or podcast and remember that like all skills, communication takes practice. Dive in. You will probably enjoy it, and so will your audience. Your CV will benefit too.

By Jane Gregory.

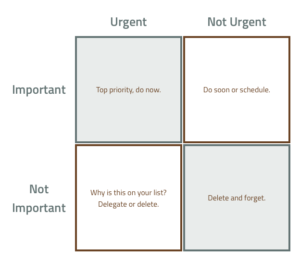

Once your To Do list has been rewritten, you can use the Urgent vs Important Matrix, or Eisenhower Matrix, to prioritise it. List your tasks in a two-by-two grid, classifying each task by whether it’s urgent or not urgent, important or not important.

Once your To Do list has been rewritten, you can use the Urgent vs Important Matrix, or Eisenhower Matrix, to prioritise it. List your tasks in a two-by-two grid, classifying each task by whether it’s urgent or not urgent, important or not important. Mentoring has developed a lot over recent years, not least because the internet means that your mentor doesn’t have be local to you anymore. Gone are the days when mentoring meant vague chats about career aspirations over coffee. Instead, we have video, voice and text chats, email, forums, and shared documents, and a level of flexibility and variety in mentor relationships that yesterday’s mentees could only dream of.

Mentoring has developed a lot over recent years, not least because the internet means that your mentor doesn’t have be local to you anymore. Gone are the days when mentoring meant vague chats about career aspirations over coffee. Instead, we have video, voice and text chats, email, forums, and shared documents, and a level of flexibility and variety in mentor relationships that yesterday’s mentees could only dream of. The ‘leaky pipeline’ is a familiar metaphor to those interested in discussions of women in STEM. The pipeline – the process of going from school to undergraduate level and on into academia until reaching professorship – is seen to leak people, particularly women and minorities, at each successive rung of the academic ladder. Despite its ubiquity, there are growing concerns that the leaky pipeline metaphor is

The ‘leaky pipeline’ is a familiar metaphor to those interested in discussions of women in STEM. The pipeline – the process of going from school to undergraduate level and on into academia until reaching professorship – is seen to leak people, particularly women and minorities, at each successive rung of the academic ladder. Despite its ubiquity, there are growing concerns that the leaky pipeline metaphor is  When you hear of companies ‘interviewing for cultural fit’, that often means that recruiters are looking for someone with a specific set of attitudes, assumptions and biases that they think will fit neatly into the existing cultural framework of the company. This can be problematic because it can damage efforts to increase diversity, resulting in a workforce that may look diverse but is actually made up of people who all think the same way.

When you hear of companies ‘interviewing for cultural fit’, that often means that recruiters are looking for someone with a specific set of attitudes, assumptions and biases that they think will fit neatly into the existing cultural framework of the company. This can be problematic because it can damage efforts to increase diversity, resulting in a workforce that may look diverse but is actually made up of people who all think the same way.