Here are just some of the Twitter highlights from this year’s Ada Lovelace Day:

Author Archives: Suw

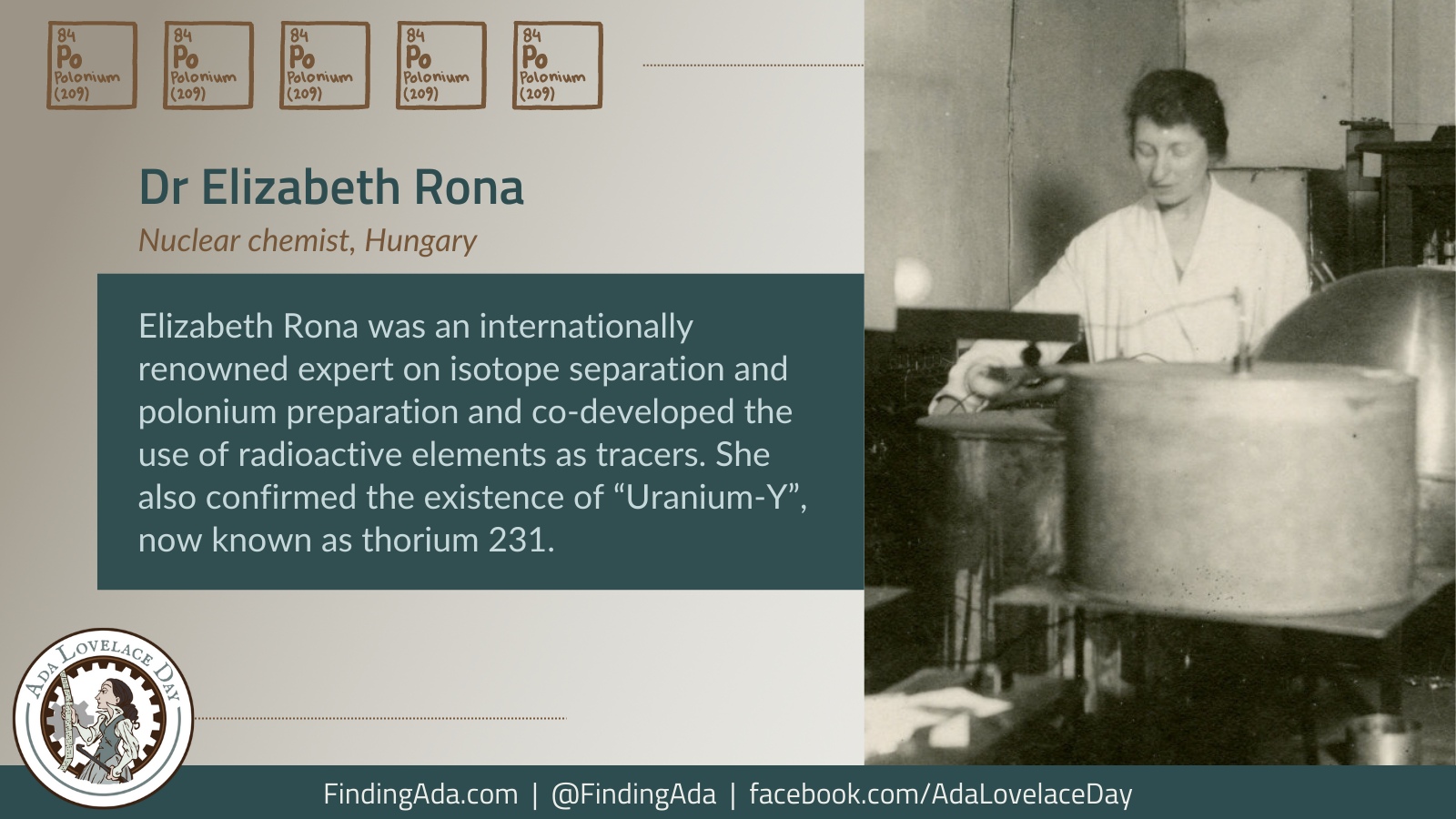

ALD22: Dr Elizabeth Rona, Nuclear Chemist

Dr Elizabeth Rona

Dr Elizabeth Rona was a nuclear chemist who became an internationally renowned expert on isotope separation and polonium preparation. She also confirmed the existence of “Uranium-Y”, known as thorium 231.

Rona was born in 1890 in Budapest. She studied chemistry, geochemistry, and physics at the Philosophy Faculty at the University of Budapest, earning her PhD in 1912. After graduation she worked at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute, Karlsruhe University and then University College London before returning to Budapest when World War I started.

She joined Budapest’s Chemical Institute, working on the diffusion of radon in water before being asked to investigate a new element known as Uranium-Y, ie thorium 231, which she successfully separated from other elements. She confirmed that it emitted beta radiation and had a half-life of 25 hours. Her work formed the basis of later mass spectrography and heavy water studies.

She worked with chemist George von Hevesy, using radioactive elements as tracers so that they could more easily study chemical reactions. They studied the diffusion of radioactive tracers through different materials, gathering the data required to calculate an atom’s size. Von Hevesy eventually won the Nobel Prize for his work on tracers, and they are now used to help diagnose cancer, heart disease and other conditions.

She became the first woman to teach chemistry at a university level in Hungary, but the communist invasion of Hungary and the subsequent anti-communist White Terror made life and work there untenable. She moved to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute to work with Otto Hahn on separating ionium (now thorium 230) from uranium until she was transferred to a more practical role in the Textile Fibre Institute. She returned to Hungary in 1923, to work in a textile factory, but disliked the work and left to join the Institute for Radium Research of Vienna in 1924.

Rona learnt how to separate polonium from Irène Joliot-Curie in Paris, returning to the Radium Institute as a well-respected expert whose skills were much in demand. She worked with several collaborators, and her work with Berta Karlik on the half-lives of uranium, thorium and actinium decay, radiometric dating, and alpha particles won them both the Austrian Academy of Sciences Haitinger Prize in 1933. She returned to Paris to work with Joliot-Curie, who died not long after. Rona herself became ill, but later went to Vienna to share what she’d learnt with a group of other researchers who were working on a wide variety of research projects.

She spent some of World War II working in Sweden and Norway, but returned to Budapest to work at the Radium-Cancer Hospital where she prepared radium for medical use.

In 1941, however, she fled to the USA, eventually finding a teaching job at Trinity College in Washington, DC before being awarded a Carnegie Fellowship, and she began studying radium seawater and sediments at the Geophysical Laboratory of the Carnegie Institute. She assisted the Manhattan Project, giving them her method for extracting polonium.

She continued her work after the war, at the United States Atomic Energy Commission and then the Oak Ridge Institute of Nuclear Studies, where she worked as a chemist and senior scientist in nuclear studies. She discovered that uranium levels in seawater are globally constant, but that thorium collects in sediments, so the decay of uranium to thorium can be used to date core samples. This method of dating is still used today.

She continued working despite two retirements, first from Oak Ridge and then from the University of Miami, returning to Tennessee in the 1970s.

Rona became aware of the dangers of radium early in her career, but her warnings of the dangers and requests for protective equipment such as gas masks were ignored and she had to supply her own. She managed to avoid radiation exposure, however, and survived at least two lab explosions.

She died in 1981, aged 91.

Further Reading

- Elizabeth Rona, Wikipedia

- Overlooked No More: Elizabeth Rona, Pioneering Scientist Amid Dangers of War, Veronique Greenwood, The New York Times, 28 August 2019

- Elizabeth Rona, the wandering polonium woman, changed radiation science forever, Brittney G. Borowiec, Massive Science, 29 December 2019

ALD22: Inge Lehmann, Seismologist and Geophysicist

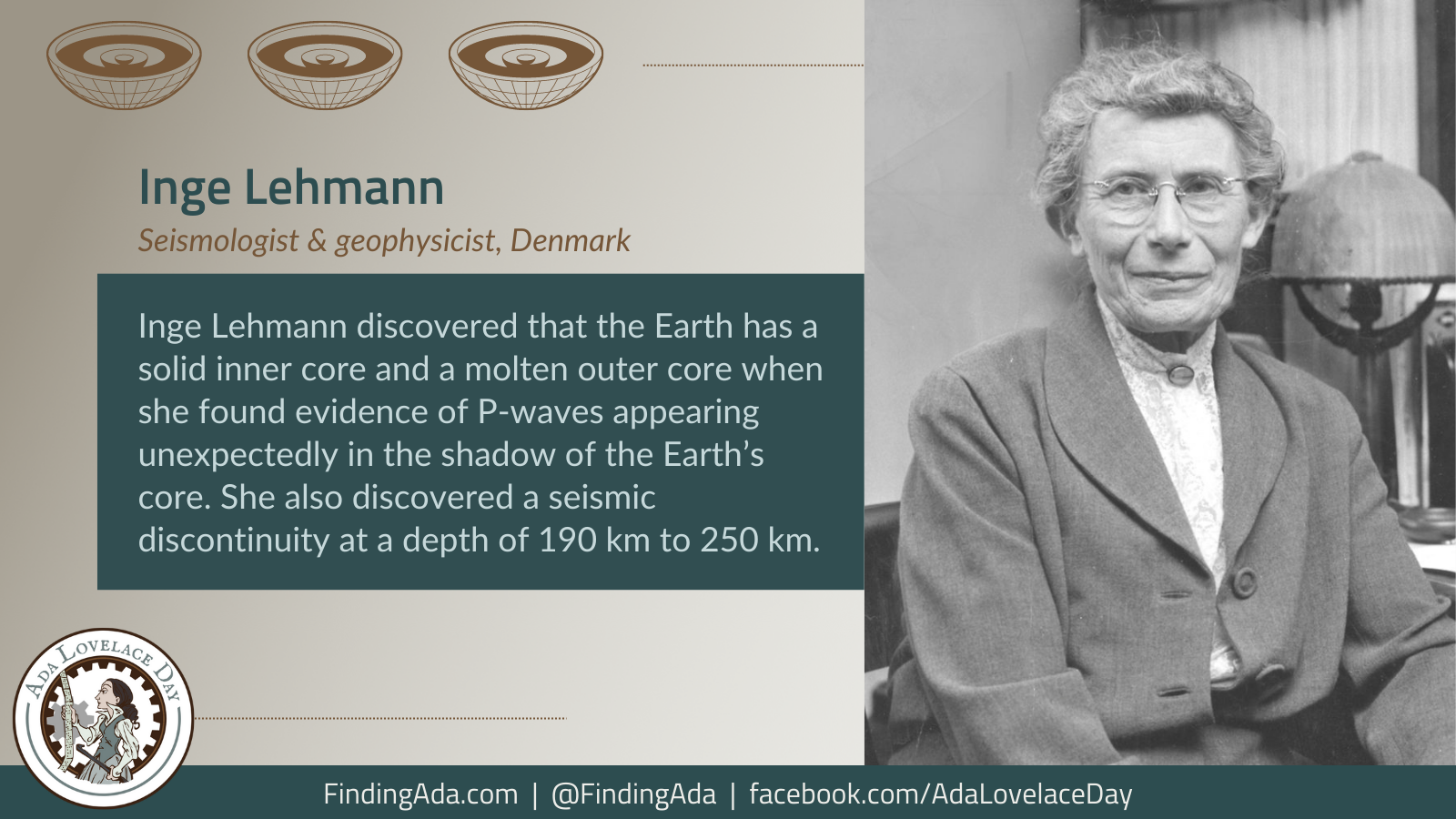

Inge Lehmann

Inge Lehmann was a seismologist and geophysicist who discovered that the Earth has a solid inner core and a molten outer core.

Born in Copenhagen in 1888, in 1907 she began studying mathematics, chemistry and physics at the University of Copenhagen and University of Cambridge, but had to take a break due to ill-health. She resumed her study of mathematics at Cambridge in 1910, before exhaustion enforced another break, eventually restarting her education at Copenhagen University in 1918, graduating in 1920.

Her interest in seismology began when she got a job as an assistant to Niels Erik Nørlund, a geodesist. She was tasked with setting up seismological observatories in Denmark and Greenland, which prompted her to study seismology. She earnt her magister scientiarum, equivalent to a master’s degree, in geodesy in 1928 and took a position as a geodesist and head of the department of seismology at the Geodetical Institute of Denmark. She was responsible for analysing the seismograph data, recording the seismic wave arrival times ready for publication in international bulletins. This data was fundamental to much of the era’s seismological research.

In 1936, she found evidence of P-waves appearing in the shadow of the Earth’s core, which she interpreted as showing that there was an inner core. At the time, it was thought that the Earth’s core was liquid, but an earthquake in New Zealand resulted in P-waves arriving at seismic stations that should have been blocked by this liquid core. Lehmann’s theory was that these P-waves had been refracted by some sort of boundary, which had to mean that there was a solid inner core and a liquid outer core.

Although this interpretation was adopted within a few years, it was not shown to be correct until 1971 when computer calculations using data from more sensitive seismographs could verify her work. Lehmann had to do all of her data collection and calculations by hand, creating boxes of cards, each with data from earthquakes around the world.

Although her work was interrupted by World War II, she served as Chair of the Danish Geophysical Society in both 1940 and 1944.

In the early 1950s, she moved to the US and began investigating the Earth’s crust and upper mantle. A decade later, she discovered a seismic discontinuity, where seismic waves change speeds, at between 190 and 250 km which is now known as the Lehmann Discontinuity. This discovery was made through “exacting scrutiny of seismic records by a master of a black art for which no amount of computerization is likely to be a complete substitute”, as geophysicist Francis Birch put it.

Lehmann received many awards over the years. She was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1969, was the first woman to win the William Bowie Medal in 1971, and was awarded the Medal of the Seismological Society of America in 1977. The American Geophysical Union began awarding the Inge Lehmann Medal to honour “outstanding contributions to the understanding of the structure, composition, and dynamics of the Earth’s mantle and core” in 1997. In 2015, the asteroid 5632 Ingelehmann was named after her, as was a new beetle species, Globicornis (Hadrotoma) ingelehmannae.

She died in 1993, aged 104.

Further Reading

- Inge Lehmann, Wikipedia

- Inge Lehmann: Discoverer of the Earth’s Inner Core, American Museum of Natural History

- Inge Lehmann, Meg Rosenburg, Trowelblazers, 16 October 2014

- How Inge Lehmann used earthquakes to discover the Earth’s inner core, Joseph Stromberg, Vox, 13 May 2015

- What Google’s doodle about Inge Lehmann is all about, Nick Statt, CNET, 13 May 2015

- Happy Birthday to Inge Lehmann, the Woman Who Discovered Earth’s Inner Core, Danny Lewis, Smithsonian Magazine, 13 May 2015

- The female scientist who discovered the core of the Earth, Lif Lund Jacobsen, Science Nordic, 15 May 2017

- Inge Lehmann: the Danish scientist who discovered Earth has a solid inner core, Brian Clegg, BBC Science Focus, 29 May 2020

- Inge Lehmann: Danish seismologist rocks Google’s earth, The Guardian, 13 May 2015

ALD22: Professor Edith Clarke, Electrical Engineer

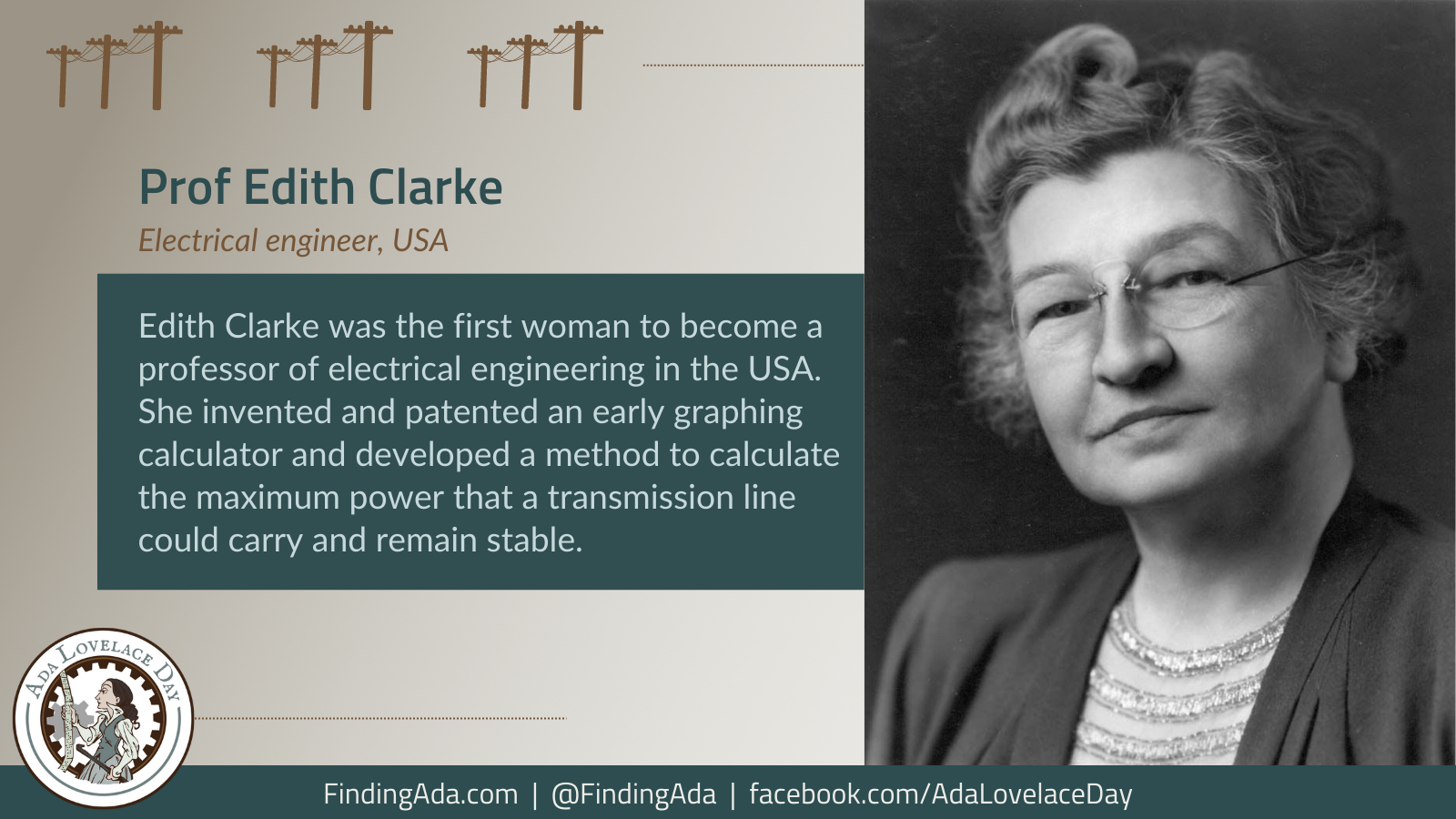

Professor Edith Clarke

Edith Clarke was an electrical engineer who was the first woman to become a professor of electrical engineering in the USA and developed a method to calculate the maximum power that a transmission line could carry and remain stable.

Clarke was born in Maryland in 1883. After being orphaned at the age of 12, she was raised by her sister and used her inheritance to study mathematics and astronomy at Vassar College. In 1911, she began studying civil engineering at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, but she took a summer job as a human ‘computer’ at AT&T at the end of her first year and enjoyed it so much that she stayed there to train other computers.

She studied electrical engineering at Columbia University in her evenings, then went on to become the first woman to earn a master’s degree in electrical engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

She found it difficult to get work as an engineer after graduation, so worked for General Electric, supervising computers. She invented and patented an early graphing calculator, called the Clarke Calculator, which solved equations involving hyperbolic functions ten times faster than other methods.

In 1921, frustrated by a lack of opportunity and equality, Clarke moved to Turkey for a year to teach at the Constantinople Women’s College. When she returned to the USA, GE offered her a position as an electrical engineer, and she became the first professional female electrical engineer in the country.

She also became the first woman to present a paper at the American Institute of Electrical Engineers’ (AIEE) annual meeting. Her paper explained how to calculate the maximum power that a line could carry and remain stable, which became very important as the energy grid grew. The AIEE also awarded her the Best Regional Paper Prize in 1932 and the Best National Paper Prize in 1941, and her work underpinned much of the industry’s understanding of how to deal with power and transmission.

Clarke worked on the West Hoover Dam, developing and installing the hydroelectric turbines.

She also lectured GE engineers, and wrote a textbook based on those lectures, Circuit Analysis of A-C Power Systems, which became a standard text for years. In it, she describes the mathematical methods for addressing power system losses and electrical equipment performance.

In 1947, she became the first female professor of electrical engineering in the USA when she joined the Electrical Engineering Department at the University of Texas at Austin. She taught at Austin until her retirement in 1957

In 1948, she became the first female Fellow of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers, and was the first female full voting member in the American Institute of Electrical Engineers. In 1954, she was given the Society of Women Engineers’ Achievement Award. In 2015, she was posthumously inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

She died in 1959, aged 76.

Further Reading

- Edith Clarke, Wikipedia

- Edith Clarke, Edison Tech Center

- US1552113A – Calculator, Google Patents, 1921

- Five Fast Facts About Engineer Edith Clarke, Pat Adams, US Department of Energy, 19 March 2015

- The Engineer Who Foreshadowed the Smart Grid–in 1921, Melissa C. Lott, Scientific American, 30 March 2016

- 10 Things You Should Know About Edith Clarke, A Badass, Pioneering Electrical Engineer, Women You Should Know, 10 February 2018

- Edith Clarke: The First Female Electrical Engineer and Professor of Electrical Engineering, Christopher McFadden, Interesting Engineering, 25 March 2018

- Member Spotlight: Edith Clarke, Electrical Engineer, Jill S. Tietjen, Society of Women Engineers, 19 February 2019

- Introducing our Female Engineer of the month: Edith Clarke, University of North Texas Society of Women Engineers, 3 August 2019

- Edith Clarke, First Female Electrical Engineer, Rediscover STEAM: Medium, 12 March 2021

- Late, great engineers: Edith Clarke – America’s first woman engineer, The Engineer, 13 July 2021

ALD22: Professor Flossie Wong-Staal, Virologist and Molecular Biologist

Professor Flossie Wong-Staal

Professor Flossie Wong-Staal, née Wong Yee Ching, 黄以静, was a virologist and molecular biologist who was the first to molecularly clone Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and created a map of its genes, which was crucial to proving that HIV causes Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS).

Born in Guangzhou, China, in 1946, she and her family fled to Hong Kong after the Communist Revolution during the late 1940s. When she was 18. Wong-Staal moved to California to study bacteriology at the University of California, Los Angeles, then moved to San Diego for her postdoctoral research before moving to the National Cancer Institute in Maryland in 1973, where she refocused her research on retroviruses.

She discovered that human T-lymphotropic virus, HTLV-1 was the cause of T cell leukaemia, proving that retroviruses can cause human disease. Her work showed that the virus affected human DNA, activating cancer-causing genes called oncogenes.

She went on to work on a new disease that was very similar to HTLV-1, and in 1975, she successfully cloned HIV. She mapped the virus’s genome which both revealed how genetically diverse HIV is, but also allowed the development of blood tests based on detection of the viral genome rather than virus antibodies. She became a world leader in HIV research, studying its genetic structure, replication strategies and regulatory mechanisms.

She published over 400 papers on human retroviruses and AIDSand was the most-cited female scientist of the 1980s. In 1990, the Institute for Scientific Information named her as the top woman scientist of the 1980s.

In 1990, she founded the Centre for AIDS Research at UCSD. Her research focused on gene therapy and on HIV-1’s relationship to Kaposi’s sarcoma, which is a common ailment for people with AIDS.

Wong-Staal became professor emerita upon retirement from UCSD in 2002, and cofounded Immusol (later iTherX Pharmaceuticals), a biopharmaceutical company, becoming its chief scientific officer. She worked there on improving drugs for hepatitis C.

She was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 2016, and Discover named her one of the 50 “most extraordinary women scientists” in 2002.

Wong-Staal died on 8 July 2020, aged 73.

Further Reading

- Flossie Wong-Staal, Wikipedia

- Flossie Wong-Staal, National Women’s Hall of Fame, 2016

- In Memoriam: Flossie Wong-Staal, Ph.D., National Cancer Institute, 13 July 2020

- Flossie Wong-Staal, Who Unlocked Mystery of H.I.V., Dies at 73, Faye Flam, The New York Times, 17 July 2020

- Flossie Wong-Staal (1946–2020), Genoveffa Franchini, Science, 11 September 2020