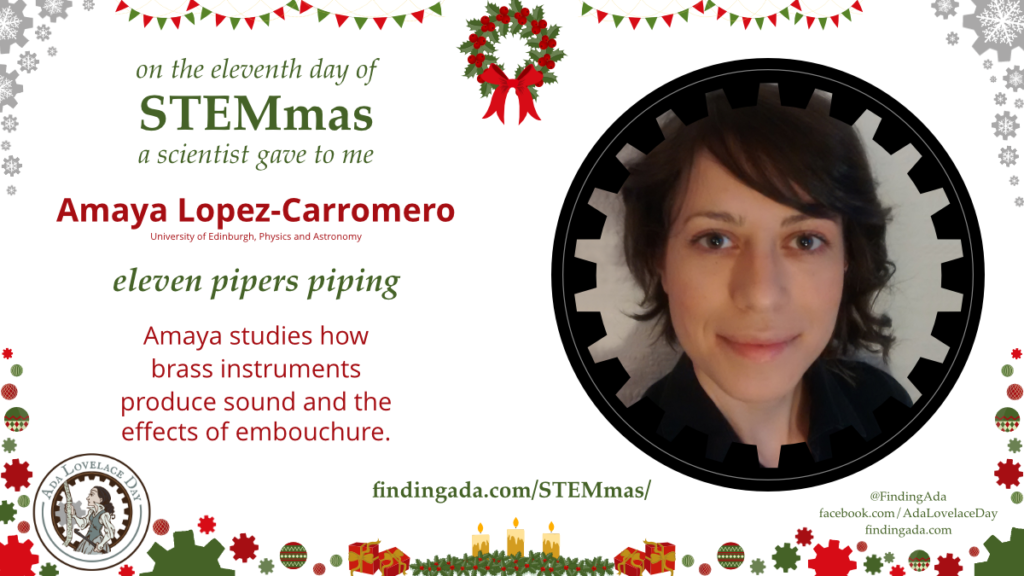

Our eleventh exceptional woman in STEM is Amaya Lopez-Carromero, who the studies the acoustics of brass instruments.

Amaya started her academic career in civil engineering, before taking a master’s in environmental and building acoustics. Also a musician, her research examines the “sound production process” in brass instruments, developing models that she then tests experimentally. In particular, she is focused on understanding “non-linear phenomena such as wave steepening in the resonator, acoustically relevant effects taking place in playing gestures, as well as some lip reed behaviours.”