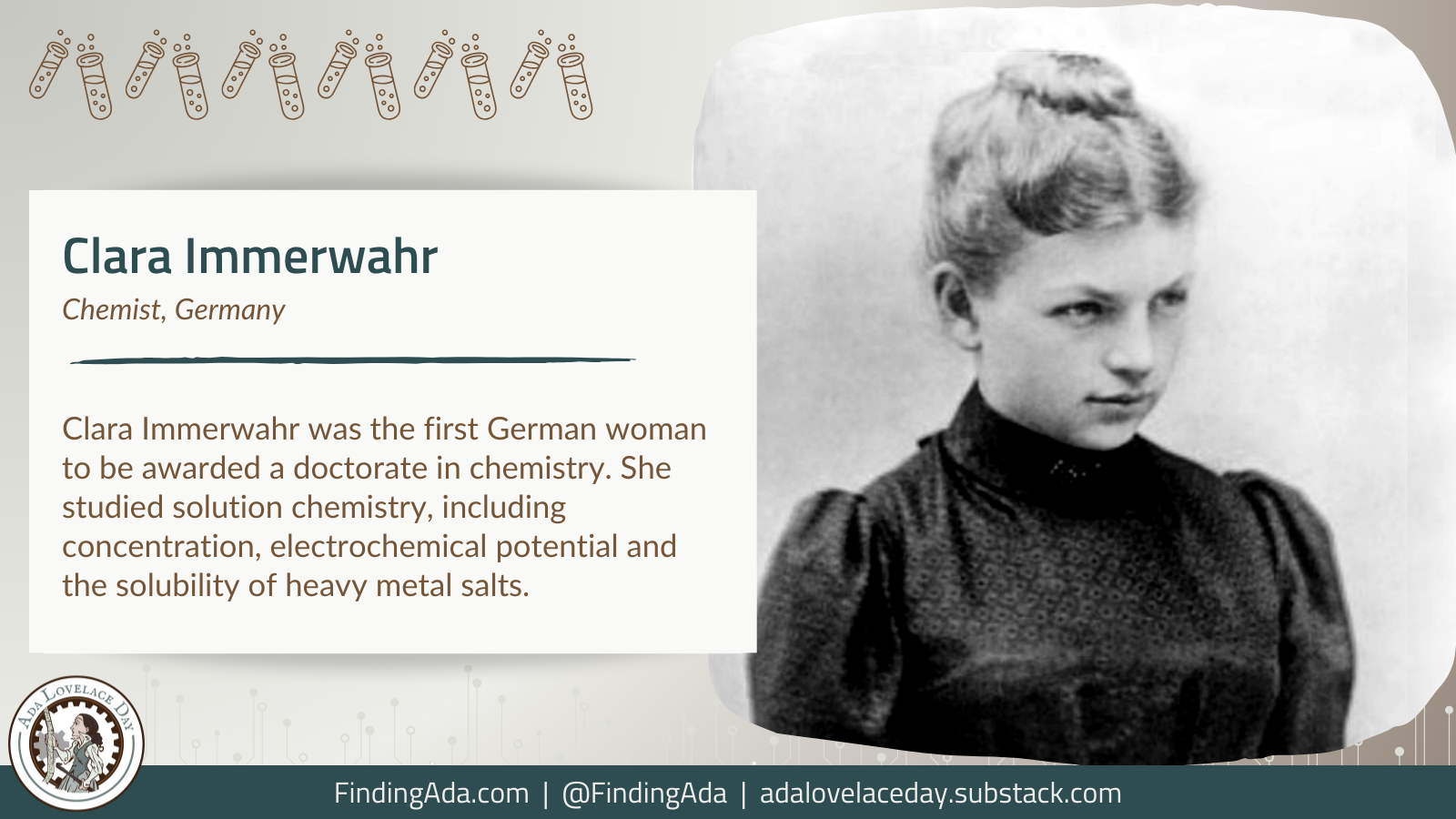

Clara Immerwahr

Clara Helene Immerwahr was a German chemist and the first woman to be awarded a doctorate in chemistry from a German university.

Born into a Jewish family on 21 June 1870 in eastern Prussia – now part of Poland – Immerwahr initially trained as a teacher, one of few higher educational paths open to German women at the time. However, she was determined to follow in her father’s footsteps and become a chemist. She embarked on gruelling private lessons and exams to gain entry to the University of Breslau to study chemistry, where she was required to attend lectures as a guest, female university students technically being barred under Prussian law.

At university, Immerwahr became fascinated by the rapidly developing field of physical chemistry. After completing undergraduate studies, she became the first woman to undertake a PhD at the University of Breslau, receiving her doctorate in chemistry magna cum laude in 1900. She reached this milestone after eight semesters of study, two more than was required for male doctoral candidates.

Immerwahr’s research focused on solution chemistry – a central focus of chemists at the turn of the 20th century – examining issues such as solubility, ion concentration and electrochemical potential. She conducted experiments involving cadmium, copper, lead, mercury and zinc and published three papers, as well an erratum and a supplement. Her investigations didn’t break new ground in chemistry, but her presence as a female scientist in a laboratory did. When Immerwahr defended her PhD thesis on the solubility of heavy metal salts in the university’s main hall in central Breslau, many young women came to watch, intrigued by the city’s “first female doctor”.

Not long after receiving her doctorate, Immerwahr married the German chemist Fritz Haber. The rigid gender norms and societal conventions of early 20th century Prussia meant this effectively marked the end of Immerwahr’s own scientific research career, although she did try to maintain her connection to science, including by delivering public presentations on the role of chemistry and physics in the household. She is also believed to have contributed to Haber’s work, albeit with scant public recognition, including by translating some of his papers into English.

The curbing of Immerwahr’s career, along with the start of World War I and the tragic accidental deaths of two close friends (including her PhD supervisor and academic mentor), are believed to have contributed to her increasing unhappiness. She died by suicide on 2 May 1915, aged 44. The same night, her husband – sometimes referred to as the “father of chemical warfare”, due to the instrumental role he played in developing poison gases for use on the battlefield – had been at a party, celebrating the “success” of the German army’s first chlorine cloud attack against Allied troops.

There has been much debate about Immerwahr’s political beliefs, and whether her death was linked to her discomfort with her husband’s role in the German war effort. What is clear is that she was a determined and ambitious scientist whose career was curtailed by the limitations placed on women’s lives at the time. Her husband would go on to win the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1918.

Further Reading

- Clara Immerwahr, Wikipedia

- Clara Immerwahr – out of her husband’s shadow, Bárbara Pinho and Anne Green, Chemistry World, 16 August 2021

- Clara Immerwahr: A Life in the Shadow of Fritz Haber, Bretislav Friedrich and Dieter Hoffmann, One Hundred Years of Chemical Warfare: Research, Deployment, Consequences, 28 November 2017

- Clara Immerwahr, Jutta Dick, Jewish Women’s Archives,

- Clara Immerwahr and the moral responsibility of science, Carmen Sánchez Cañizares, Society of Spanish Researchers in the United Kingdom, 10 February 2022

- Clara Immerwahr: Science’s Tragic and Surprisingly Modern Heroine, Kristen Vogt Veggeberg, Nursing Clio, 16 June 2020

Written by Moya Crockett, with thanks to Stylist for their support.