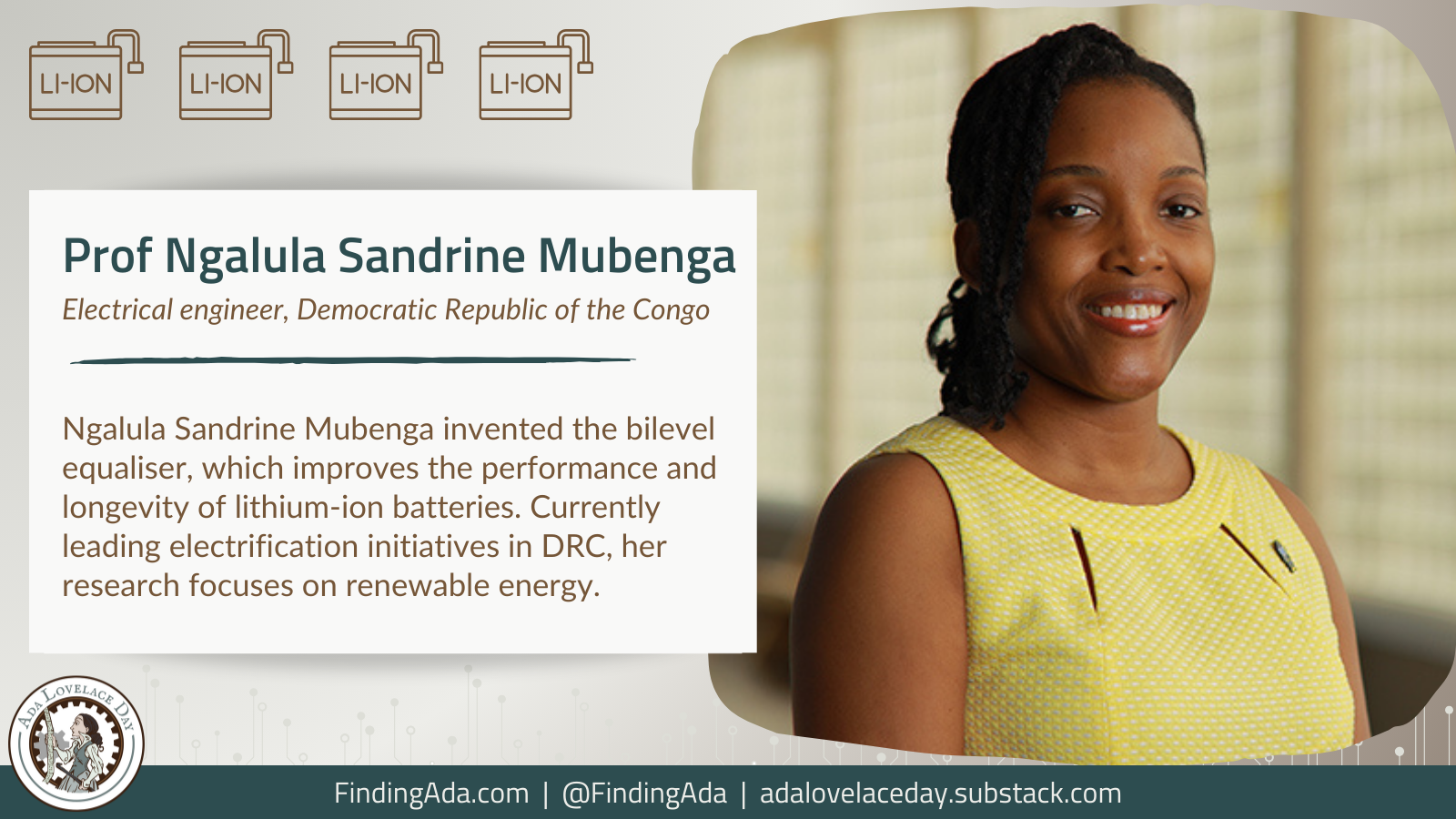

Professor Ngalula Sandrine Mubenga

Professor Ngalula Sandrine Mubenga is an electrical engineer whose pioneering research into battery management systems identified ways to increase the capacity and longevity of batteries.

Mubenga was born in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and had a medical scare aged 17 that drove home to her the importance of reliable energy. She had been hospitalised in Kikwit with appendicitis and needed urgent surgery, but the city had run out of power. It took three agonising days for Mubenga’s father to find enough fuel for the surgery to be performed – an experience that she has said inspired her to pursue a career in electrical engineering.

Today, Mubenga is an engineer and assistant professor of electrical engineering technology at the University of Toledo in the US, whose research focuses on sustainable and renewable energy (including solar power, electric vehicles and battery management).

She conducted her award-winning research into batteries as a doctoral student at the University of Toledo, where she developed a new kind of equaliser (a tool that can be used to rejuvenate tired batteries or to prevent batteries from becoming tired). Mubenga invented a bilevel equaliser, the first to combine an active and low-cost passive equaliser, that could be used to extend the life of lithium-ion batteries.

Mubenga is also an entrepreneur and philanthropist. In 2011, she founded SMIN Power Group LLC, a company that aims to help Africans overcome power outages. SMIN designs and installs renewable energy devices and solar systems – including public lighting and water pumping projects – in communities, schools and hospitals across the DRC. It also provides financial support to African students who are studying science and working on climate change solutions.

In 2018, Mubenga launched the STEM DRC initiative (where she still serves as president), a not-for-profit organisation that works to stimulate social and economic development in the DRC by promoting STEM education and providing college scholarships for Congolese students.

Mubenga currently leads electrification initiatives in the DRC as Director General of the country’s Electricity Regulatory Agency, a role to which she was appointed by the government in 2020. Previously, she served on the board of directors for Société Nationale d’Électricité (the DRC’s national energy company). She now balances her position as a DRC government official with her post at UoT, where she continues to teach and conduct research.

Mubenga’s awards and honours include being recognised as one of the Most Important Black Women Engineers by DesignNews and Engineer of the Year by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers in 2018. The same year, her battery research won the IEEE National Aerospace and Electronics Conference Best Poster Award.

You can follow her work here:

Twitter: @NgalulaPe

Website: drmubenga.com

Further Reading

- Ngalula Mubenga, Wikipedia

- Women Champions in the Energy Sector, Power Africa

Written by Moya Crockett, with thanks to Stylist for their support.