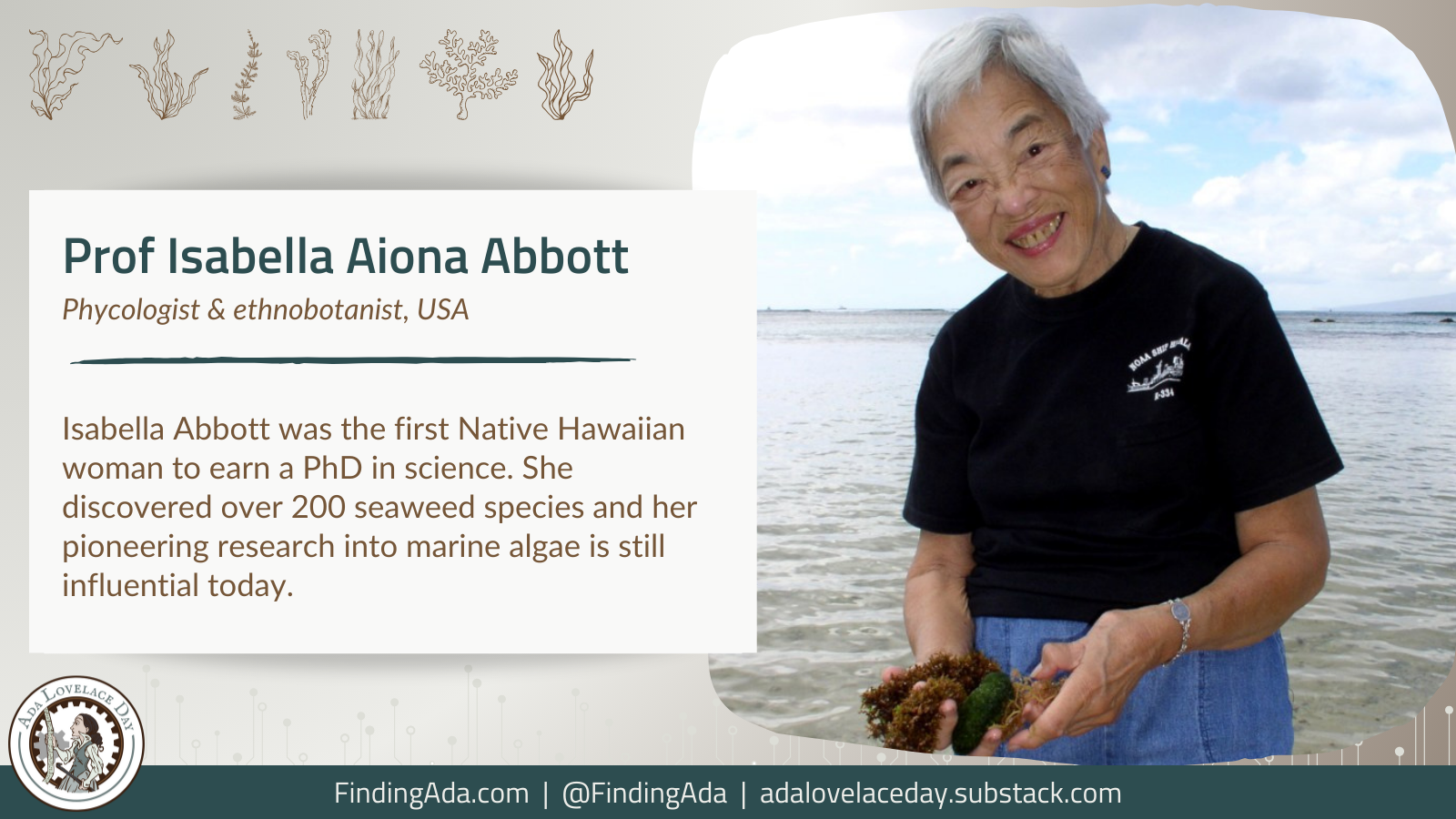

Professor Isabella Aiona Abbott

Isabella Aiona Abbott was a phycologist, ethnobotanist and educator from Hawaii. The first Native Hawaiian woman to receive a PhD in science, she was a leading expert on Pacific marine algae and the first woman and person of colour to be appointed as a full-time biology professor at the University of Stanford. Over the course of a long career, she was credited with discovering hundreds of species of seaweed.

Abbott was born Isabella Kauakea Yau Yung Aiona in Hana, Maui, on 20 June 1919 (Abbott was her married name). When she was young, her mother opened her eyes to the diversity and uses of Hawaii’s native plants – particularly seaweed, edible varieties of which they used in recipes at home. After a bachelor’s degree and master’s in botany, Abbott gained her PhD in algal taxonomy from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1950.

By the time she earned her doctorate, Abbott was 31 and married. Academic posts were not forthcoming for female scientists in the early 1950s, and Abbott took a break from her research career when her daughter was young. But in 1966, she was hired as a research associate and lecturer at the Hopkins Marine Station in California, run by Stanford University – making her the university’s first Native Hawaiian faculty member.

Abbott went on to build a formidable reputation as one of the world’s foremost experts on algae, especially that found in the Pacific marine basin. In 1972, Stanford promoted her directly to full professor of biology. Drawing on Native Hawaiian knowledge and oral histories, a rarity in the academic study of oceans at the time, Abbott’s research uncovered ancient uses for newly-named marine algae. She was one of the first scientists to highlight the vital role seaweed forests play in healthy marine ecosystems.

Today, Abbott’s work is recognised as laying the foundations for modern research into seaweed, covering everything from its use in human nutrition to its potential for sequestering carbon and limiting ocean acidification. She was the GP Wilder Professor of Botany at Stanford from 1980 before retiring in 1982 and moving back to Hawaii with her family. The University of Hawaii appointed her professor emerita of botany, and she continued to research algae and native plants and established an undergraduate degree in ethnobotany (the interaction of humans and plants). Abbott was elected a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1998.

By the time she passed away on 28 October 2010 at the age of 91, Abbott had single-handedly discovered more than 200 species of seaweed. Many were named after her, including the red algae genus of Abbottella. She had also authored over 150 scientific publications and eight books, including the influential Marine Algae of California. Several of her specimens remain part of the botany collections in the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C.

Abbott was awarded the Darbaker Prize by the Botanical Society of America in 1969, the Charles Reed Bishop Medal in 1993 and the Gilbert Morgan Smith Medal from the National Academy of Sciences in 1997. In 2005, she was named a “Living Treasure of Hawaiʻi”, and received a lifetime achievement award from the Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources for her studies of coral reefs in 2008.

Further Reading

- Isabella Abbott, Wikipedia

- Trailblazing marine botanist Isabella Aiona Abbott honored at Hopkins Marine Station, Chris Peacock, Stanford Report, 26 May 2022

- How the ‘First Lady of Seaweed’ Changed Science, Shoshi Parks, Atlas Obscura, 11 March 2022

- Marine Botanist Isabella Aiona Abbott and More Women to Know this Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, Healoha Johnston & Sara Cohen, Smithsonian American Women’s History Museum, 3 May 2021

Written by Moya Crockett, with thanks to Stylist for their support.