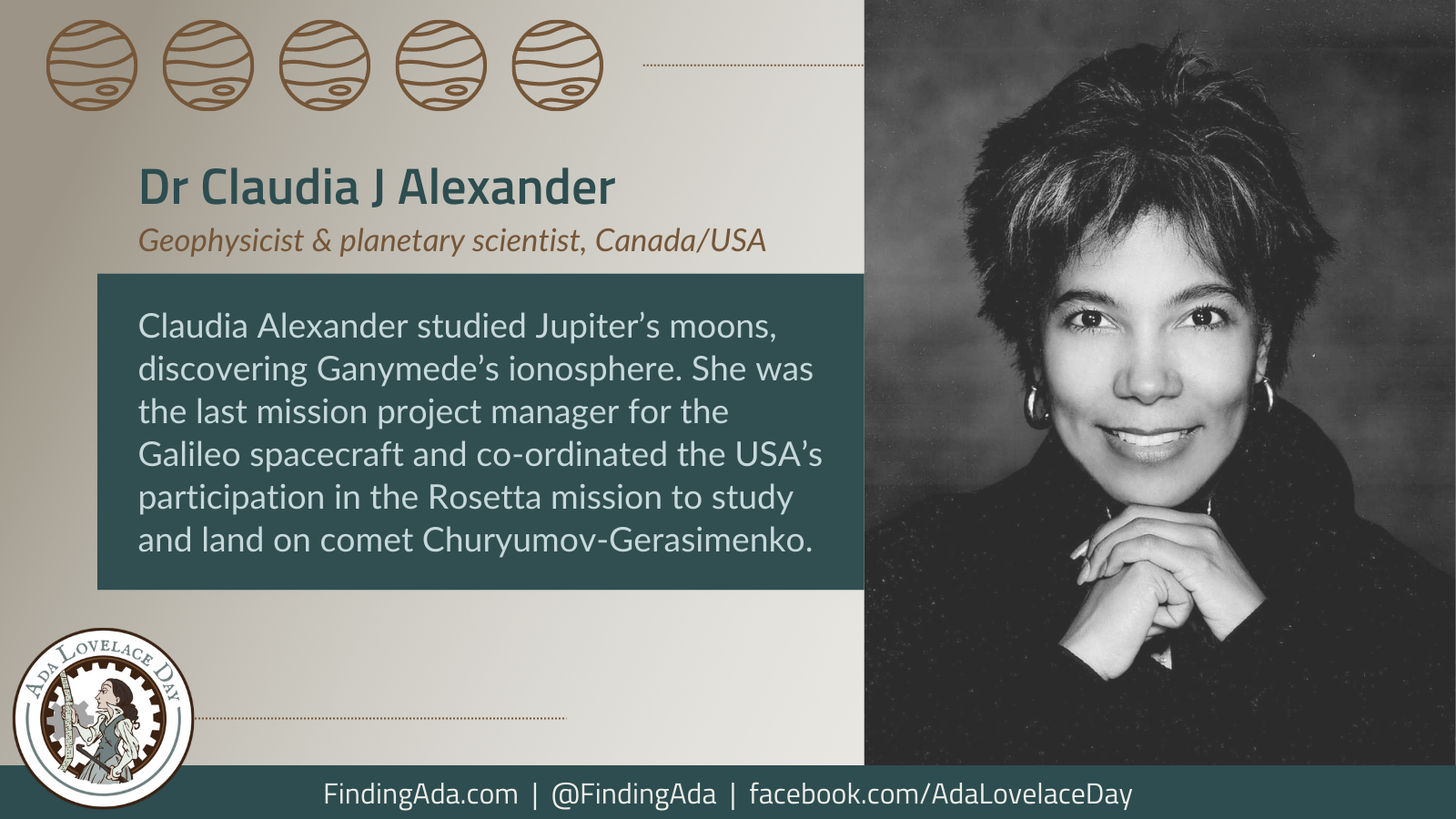

Dr Claudia J Alexander

Dr Claudia J Alexander was a Canadian-American geophysicist and planetary scientist who worked for the United States Geological Survey (USGS) and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

After getting her PhD in atmospheric, oceanic and space sciences, Alexander began working at the USGS studying plate tectonics, then at the Ames Research Center studying Jupiter’s moons. In 1986, she began working at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory working first as a science coordinator for the plasma instrument on the Galileo spacecraft, before becoming its last mission project manager and overseeing its final plunge into Jupiter’s atmosphere in 2003.

It was during her tenure that Galileo discovered Ganymede’s ionosphere, forcing Alexander to completely rethink her models that showed Ganymede was “frozen solid”. She said of the discovery, “It was an exciting moment to experience something that changed my whole way of thinking. I’ve never been so happy to be wrong before!”

From 2000 until her death, Alexander was in charge of the USA’s contribution to the European Space Agency’s Rosetta mission to study and land on comet Churyumov-Gerasimenko. She was responsible for the instrumentation that collected data such as temperature, as well as overseeing the spacecraft’s tracking and navigation support, which was provided by NASA’s Deep Space Network.

Alexander had a wide variety of interests, studying comet formations, magnetosphere, solar wind, and the planet Venus. She was also a science fiction writer and published children’s books about science under the name EL Celeste.

In 1993, Alexander was named woman of the year by the Association for Women Geoscientists, and in 2003 she received the Emerald Honor for Women of Color in Research & Engineering from Career Communications Group.

In 2015, the Rosetta mission’s team named a gate-like feature on comet Churyumov-Gerasimenko after Alexander, calling it the C Alexander Gate. In 2020, The Division for Planetary Sciences of the American Astronomical Society named a prize for mid-career planetary scientists after her.

Further Reading

- Claudia Alexander, Wikipedia

- Claudia Alexander (1959-2015), NASA: Solar System Exploration,

- Claudia Alexander, American Physical Society

- Claudia J. Alexander Prize Will Honor Achievements By Mid-Career Planetary Scientists, Division for Planetary Sciences of the American Astronomical Society

- Claudia Alexander, Beloved NASA Project Scientist, Dies at 56, Sarah Lewin, Space, 21 July 2015

- Interview with NASA Rosetta scientist Claudia Alexander, Euronews Next, 22 July 2015

- Comet feature named after late NASA scientist Claudia Alexander, Phys.org, 30 September 2015

- Claudia Alexander, African American Literature Book Club

- Dr. Claudia Alexander – Planetary Scientist, Davitia James, POC Squared, 12 April 2021